Hide-seek-hide? The effects of financial secrecy on cross-border financial assets

Patrimoine transfrontalier

Cette page présente une sélection de sources de données publiques et non publiques utilisées dans les recherches sur la richesse transfrontalière cachée. Avec l’amélioration de la disponibilité des données, la richesse détenue dans les centres financiers offshore est de mieux en mieux documentée. Dans le même temps, l’identification des véritables propriétaires d’actifs non déclarés reste un défi majeur. Les statistiques internationales regroupent souvent les investisseurs institutionnels, les entreprises et les particuliers et ne tiennent pas compte des différentes couches de sociétés écrans et de trusts qui contribuent à dissimuler la propriété effective. En outre, la richesse privée n’est pas seulement cachée dans de petits centres financiers offshore, mais aussi dans de grandes économies offrant certaines options de secret aux investisseurs étrangers. Dans les grandes économies, les actifs cachés provoquent beaucoup moins d’anomalies statistiques et sont donc plus difficiles à identifier.

What do you want to know?

- Bank deposits held in tax havens

- Who owns fiduciary deposits in Switzerland?

- European wealth discovered in the Swiss Leaks

Publicly available data

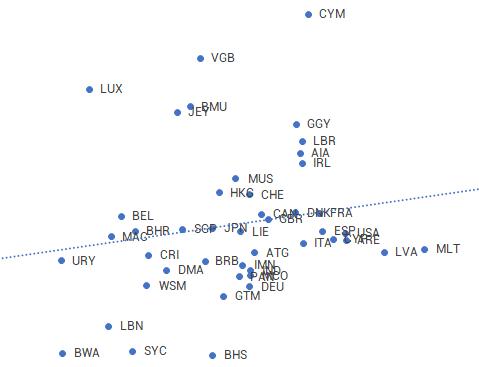

The Locational Banking Statistics provided by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) cover to date 48 jurisdictions with major international financial centres (British spelling in the paragraph above). In these countries, banks are required to report their foreign positions to the Central Bank, which shares them with the BIS in aggregate form. The locational banking statistics comprise quarterly bilateral data about the cross-border bank deposits of deposit holders from more than 200 countries. As most international financial flows are concentrated in the 48 reporting jurisdictions, the BIS estimates that the database captures around 95% of cross-border banking activities. Bilateral data can be broken down into ownership by banks and non-banks. The latter category includes cross-border deposits by companies and private households which are frequently used in research on individuals’ cross-border tax evasion.

Advantages of the locational banking statistics include the high quality of the data and wide coverage incorporating many tax havens. A potential disadvantage for tax research is that deposits are allocated to counterparty countries based on immediate ownership and not to the country of residence of the ultimate owner. As tax evasion schemes sometimes involve several layers of shell companies registered in various jurisdictions, a significant share of tax haven deposits is owned by entities in other tax havens and cannot be traced back to the country of residence of the true beneficial owners.

Access the data

The data can be accessed on the website of the BIS, via this link. It can either be downloaded or visualized through an online statistics explorer. For example, to reproduce the figure above (“cross-border deposits by non-banks in selected offshore jurisdictions”) click on the BIS Statistics Explorer for Table A2.1 and then choose the column Non-bank sector >> Total >> Liabilities.

Recent studies based on the Locational Banking Statistics

Langenmayr & Zyska 2021 (read more); Ahrens et al. 2020 (read more); Balakina et al. 2016 (read more)

The International Investment Position of a country is a statistical statement that describes, at one point in time, the value of financial assets owned by this country’s residents as claims over non-residents and that of residents’ liabilities to non-residents. For example, it presents the value of foreign stocks, obligations, and other securities owned by French residents, as well as the value of all French stocks, obligations, and other securities held abroad. The CPIS is a voluntary survey by the IMF in which countries report their holdings of foreign portfolio investments. As the bulk of personal financial wealth is held in the form of portfolio investment, the IIP and CPIS statistics are key resources for research on offshore wealth and tax evasion by individuals.

The debtor-reported liabilities from the IMF IIP data were found to be inconsistent with the creditor-derived liabilities from the CPIS. This might partly be due to the underreporting of assets held through shell companies in tax havens. For example, a corporation might correctly report a liability to a foreign investor located in a tax haven. If this investment was made through a shell company by a non-haven resident who does not declare ownership in his or her country of residence, neither the tax haven nor the true country of residence would declare the ownership of the asset. As a result, the global amount of reported liabilities exceeds the global amount of reported assets. This discrepancy has been used by several authors to estimate the amount of wealth hidden offshore.

Access the data

The website of the IMF provides access to IIP data here and CPIS data here .

Studies based on IIP and CPIS data

Zucman 2013 (original article); de Simone et al. 2019 (read more); Pellegrini et al. 2016 (read more); Vellutini et al. 2019 (read more)

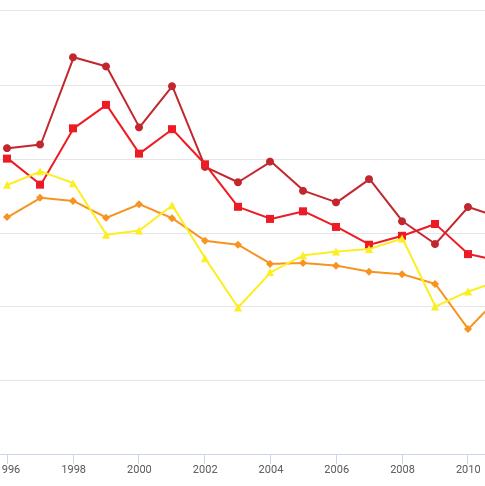

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) publishes detailed annual and monthly statistics about the deposit accounts and the portfolio of securities managed by Swiss banks, for both residents and foreign investors. In particular, monthly data about the securities held in bank custody accounts allow distinguishing resident and non-resident account holders, the different categories of securities being held (shares, units in collective investment schemes, bonds, etc.), or the nature of the investor (institutional, private or commercial).

The SNB also provides information about the fiduciary deposits held by foreign investors in Swiss banks. These deposits are held off the balance sheet of Swiss banks, which only act as intermediary agents by investing the funds in foreign money markets and transmitting resulting interests back to the account holder. The SNB has notably shared breakdowns of these fiduciary deposits by country of residence of the account holder since 1976.

Access the data

Monthly banking statistics of the SNB can be accessed via this link. The annual statistics datasets are available here. Data on fiduciary deposits by country of ownership can be found here.

Studies based on banking statistics of the SNB

Zucman 2013 (original article); Alstadsæter et al. 2018 (read more)

Leaked confidential data from banks or other private wealth managers have allowed unprecedented insights into the world of offshore tax evasion. The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) has collected, prepared, and analysed information from leaks and provides public access to the data online.

The Swiss Leaks website presents information from HSBC Switzerland which was leaked in 2007. The exposure revealed a complete list of HSBC Switzerland’s 30,412 clients and of their holdings, which amounted to $118.4 billion. An advantage of the data is that the true beneficial owners behind shell companies were identified allowing for an accurate country-by-country breakdown of asset ownership. On the Swiss Leaks website, the ICIJ provides a ranking of countries by the number of clients or by the amount of wealth held in HSBC Switzerland, as well as analyses of selected personalities and news coverage.

The offshore leaks database includes ownership data for more than 785,000 offshore companies and trusts from the Panama Papers, Paradise Papers, and the 2013 ICIJ Offshore Leaks investigation. The data were extracted from confidential documents of private offshore wealth managers including the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca, the offshore service providers Portcullis Trustnet and Commonwealth Trust Limited, and the offshore law firm Appleby. The corporate registries of Aruba, Bahamas, Barbados, Cook Islands, Malta, Nevis, and Samoa were also investigated.

The database allows users to search the ownership data by country or to search for people, companies, and addresses connected to offshore entities, for example, to investigate the offshore links of a specific person or to identify the true owners behind a letterbox company.

Recent research based on leaked data

The data were mostly used by investigative journalists to reveal ownership links to tax havens of politically exposed persons. Leaked data were also used in academic research, for example by Caruana-Galizia & Caruana-Galizia 2016 (go to the original article), Alstadsæter et al. 2018 (read more), and Alstadsaeter et al. 2019 (read more).

Access the data

The Offshore Leaks Database can be accessed following this link.

The Swiss Leaks website can be accessed following this link.

Administrative data sources

National administrations may conduct a variety of audits to verify the compliance of individual taxpayers and estimate the scale of abusive practices. On the one hand, random audits consist of investigating the income and wealth reporting of representative taxpayers, selected randomly. On the other hand, administrations can run targeted audits, which are specifically directed towards taxpayers deemed as “high risk” based on a predefined set of criteria. For example, in the US, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) conducts the Global High Wealth program, which is a targeted audit focused on individuals and corporations with assets or earnings in the tens of millions of dollars.

The aim of audits is generally twofold. First, they (especially random audits) are generally designed to estimate and monitor the so-called “tax gap”, i.e. the discrepancy between the amount of tax that should theoretically be collected and the amount that is paid. Second, in line with classical crime deterrence models, introducing national audit programs is a way to increase the probability of detection perceived by tax evaders and can therefore serve, at least theoretically, as a threat to curb tax evasion practices.

Making audit data available to researchers would facilitate research progress on many tax-related issues such as the scale and distribution of tax evasion and the effectiveness of enforcement measures. Among the few European countries which have shared audit data with researchers are Denmark, the Netherlands, and Norway.

Recent studies based on audit data

Guyton et al. 2021 with data from the U.S. (read more); Alstadsæter et al. 2019 with data from Denmark (read more); Hebous et al. 2020 with data from Norway (original article); Leenders et al. 2021 with data from the Netherlands (read more); Durán-Cabré et al. 2019 with data from Catalunia (original article)

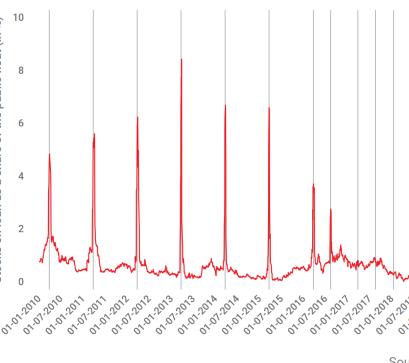

Another tool that national administrations use to disincentivise tax evasion, collect data and better understand the phenomenon of tax evasion is the introduction of voluntary disclosure schemes. As part of these programs, tax evaders can disclose the undeclared assets that they hold offshore and benefit from preferential penalties or complete amnesty. While the effectiveness of these mechanisms in preventing non-compliant behaviours can be questioned, they are a valuable source of information for researchers.

Making data from voluntary disclosures available for research could improve estimates on the scale and distribution of offshore wealth and facilitate the evaluation of policy measures against tax evasion. Among the few European countries which have shared voluntary disclosure data with researchers are Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden.

Recent studies based on voluntary disclosure data

Pellegrini et al. 2016 with data from Italy (read more); Johannesen et al. 2020 with data from the U.S. (original article); Guyton et al. 2021 with data from the U.S. (read more); Andersson et al. 2019 with data from Norway (original article); Leenders et al. 2021 with data from the Netherlands (read more)

Ceci pourrait également vous intéresser

Tax deficits and the income shifting of U.S. multinationals

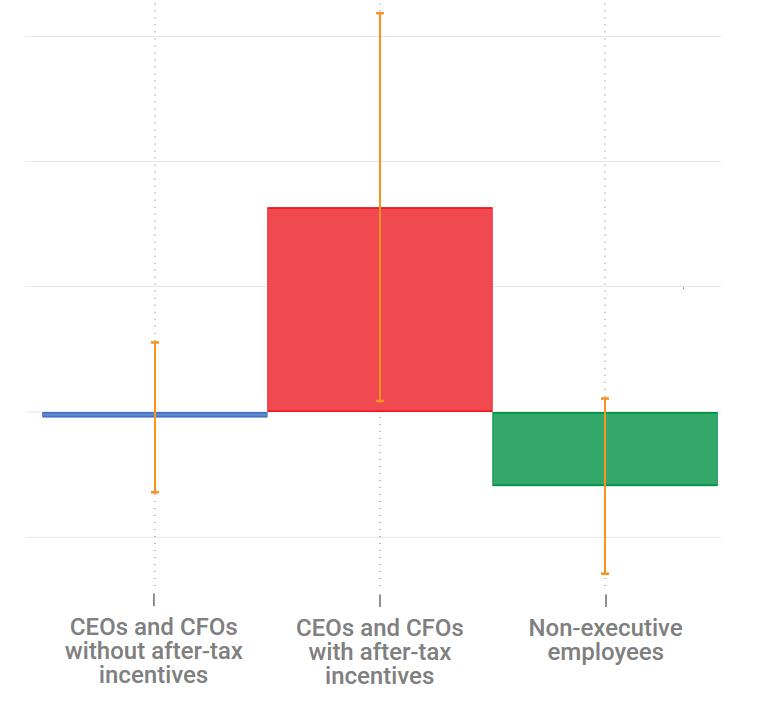

Profit shifting, employee pay, and inequalities: evidence from US-listed companies

Welfare Effect of Closing Loopholes in the Dividend-Withholding Tax: The Case of Cum-Cum and Cum-Ex Transactions