Hide-seek-hide? The effects of financial secrecy on cross-border financial assets

Taux d’imposition et classements

Le taux d’imposition légal n’est qu’un des nombreux éléments qui déterminent les paiements d’impôts des sociétés. La charge fiscale des sociétés dépend aussi fortement de la définition des bénéfices imposables. Ceux-ci peuvent différer des bénéfices financiers en raison des déductions pour amortissement, des paiements d’intérêts déductibles, des déductions pour fonds propres des sociétés et des régimes fiscaux spéciaux tels que les incitations à la R&D ou les boîtes à brevets. En outre, le report des pertes en avant et en arrière peut réduire le montant des bénéfices imposables d’une année donnée.

Outre toutes les composantes juridiques de l’imposition des sociétés, l’interprétation de la loi peut également jouer un rôle. Par exemple, les accords dits “Sweetheart deals”, rendus célèbres par le scandale LuxLeaks, comprenaient des accords spéciaux entre les autorités fiscales et certaines multinationales sur la manière de définir le bénéfice imposable et réduisaient considérablement leurs paiements d’impôts. Enfin, l’évitement fiscal peut réduire l’imposition d’une manière non prévue par le législateur, par exemple lorsque des multinationales déplacent leurs bénéfices vers des juridictions à faible fiscalité. Étant donné que ce type d’arbitrage réglementaire n’est pas accessible aux entreprises purement nationales, dans certains cas, il est judicieux d’analyser également séparément les paiements d’impôts des multinationales.

La liste suivante donne un aperçu des mesures de l’impôt sur les sociétés qui pourraient être utiles pour comprendre combien d’impôts les sociétés paient en Europe ou quels États membres pourraient être considérés comme des pays à “forte imposition” ou à “faible imposition”. Chaque indicateur a ses forces et ses limites, en fonction de la question que vous posez.

Choisissez un indicateur

Les taux légaux d'imposition des sociétés les plus élevés définissent le taux auquel les bénéfices des sociétés sont imposés, y compris les impôts à différents niveaux de gouvernement et les surtaxes. Un taux d'imposition légal élevé n'implique pas automatiquement une imposition effective élevée, car il peut être associé à une définition étroite de l'assiette fiscale. Vous trouverez plus d'informations ci-dessous.

Les taux d'imposition effectifs prévisionnels sont des taux d'imposition basés sur des modèles. Ils combinent les informations sur les taux d'imposition légaux avec d'autres dispositions fiscales qui affectent la définition de l'assiette fiscale, comme les déductions pour amortissement pour différents types d'actifs. Vous trouverez plus d'informations ci-dessous.

Les taux d'imposition effectifs rétrospectifs estiment le montant de l'impôt sur les sociétés payé par les entreprises par rapport à leurs bénéfices. Ils peuvent être basés sur différentes sources de données et intègrent implicitement tout ce qui pourrait entraîner des écarts entre le taux d'imposition légal et les paiements d'impôts réels des entreprises. Vous trouverez plus d'informations ci-dessous.

Le score des paradis fiscaux, qui fait partie de l'indice des paradis fiscaux pour les entreprises élaboré par le Tax Justice Network, combine des informations sur les règles fiscales générales d'un pays avec des caractéristiques spécifiques du système fiscal qui facilitent l'évasion fiscale des sociétés multinationales. Un score plus élevé implique un risque plus élevé d'abus fiscal des entreprises. Plus d'informations ci-dessous.

L'indice d'attractivité fiscale élaboré par l'Institut de fiscalité et de comptabilité de la LMU de Munich (Schanz et al., 2017) saisit des informations sur les taux d'imposition légaux et un large éventail de dispositions fiscales générales au niveau des entreprises. L'indice va de 0 à 1. Une valeur d'indice plus élevée indique une plus grande attractivité fiscale, c'est-à-dire un niveau plus faible d'imposition des sociétés. Plus d'informations ci-dessous.

What does this indicator measure?

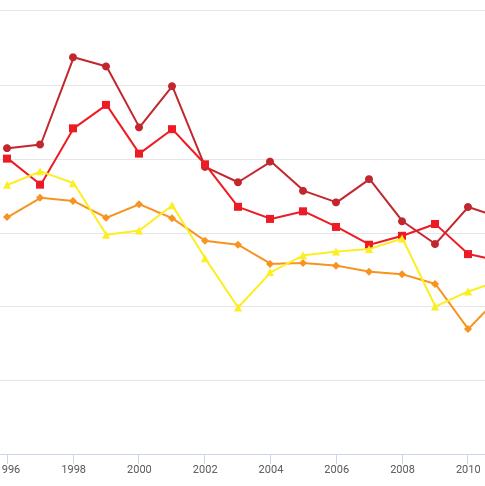

Statutory corporate tax rates are the most straightforward indicator for international comparisons. They are easy to understand, available for all countries and for long periods. That is why they are frequently used in international tax research and most often referred to in public debates on taxation. A high statutory tax rate does not in all cases come along with high effective taxation, for example, if the defined tax base is narrow or if preferential rates apply for certain types of income.

- The EU Commission provides top statutory corporate income tax rates (including surcharges) for all member states reaching back to 1995. [Go to the EU data]

- Alternative data sources are the OECD or KPMG that also include non-European countries. [Go to OECD data] [Go to KPMG data]

Forward-looking effective average tax rates (EATR) capture information on statutory tax rates and other tax provisions at the corporate level such as capital allowances for different asset types or other tax incentives. They are based on a microeconomic model of a hypothetical investment project to calculate the average tax contribution a firm makes on an investment project. For example, the return on an investment project would normally be taxed at the statutory rate. But as the company bought a new machine to make this investment, a certain percentage of its expenditure can be deducted from the taxable profit. This reduces the tax effectively paid. Researchers also calculate EATR for different financing choices because interest payments can usually be deducted from corporate profits while dividend payments to shareholders are not tax-deductible. The EATR measure at company level can be extended to incorporate tax provisions at the shareholder level (personal level) that might affect investor’s choices such as the taxation of dividends received from the cooperation or capital gains realized from disposal of shares in the cooperation. Theoretically, most features of the tax system could be incorporated into an EATR model. However, only standard tax provisions are included to facilitate inter-country comparisons usually (e.g., only five very common asset types are considered).

The EU Commission provides EATR prepared by the ZEW which combine information on capital allowances for different asset types and funding sources, the tax treatment of inventories, personal income taxation of dividend, interest and capital gains, and real estate tax. [Go to EU EATR data]

The OECD provides EATR data that focus on features of the corporate tax system only and include asset-specific capital allowances and the average tax treatment of different funding sources. [Go to OECD EATR data]

Backward-looking average effective tax rates estimate how much individual companies have paid in corporate income tax relative to their profits. They can be estimated based on various sources such as companies’ balance sheet data or data from multinational corporations’ country-by-country reports. An advantage of this type of ETR is that they implicitly measure to what extent the tax rules reduce the tax effectively paid when applied to real company cases. This includes the effects of all legal provisions that define the corporate tax base but also other factors such as the interpretation of the law by tax authorities and companies. A disadvantage of this approach is that financial profits and taxable profits are different by definition and companies usually do not provide enough information to sufficiently adjust for these differences, e. g. by excluding non-taxable equity income but including taxable interest income.

Individual company ETR can thus fall short of the statutory tax rate for many reasons, among which are mismeasurement of profits that should be subject to tax; a narrow definition of the tax base according to the tax law; a lot of gross income from activities taxed at preferential rates; a generous application of the tax law by the tax authority or manipulation of taxable profits by the company. As a result, interpretation of backward-looking ETR needs to be careful, especially when based on a low number of observations. Still, a large discrepancy between statutory rates and backward-looking effective tax rates at the country-level can indicate that companies pay much less tax than most people would assume.

- Download a table with ETR estimates for multinational corporations based on OECD CbCR data by García-Bernardo & Janský (2021). [xlsx]

- See also the literature summary of the related research paper. [summary]

- Other ETR estimates for multinational corporations in the EU based on ORBIS by García-Bernardo, Tørsløv and Janský can be found in the research paper “Multinational corporations’ effective tax rates: evidence from Orbis”. [go to the original paper]

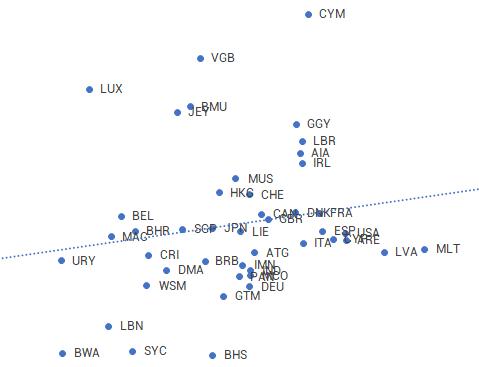

Why are some countries attractive profit shifting destinations even if they have moderate corporate tax rates? The haven score as part of the corporate tax haven index developed by the Tax Justice Network combines information about the general tax rules of a country with specific features of the tax system that facilitate tax avoidance by multinational corporations. These include legal loopholes, a lack of transparency and avoidance measures, and the aggressiveness of the tax treaty system. A high haven score implies that the jurisdiction’s tax and financial system allow a high scope for corporate tax abuse. TJN deems a high scope for corporate tax abuse more problematic the more multinational financial activity a country hosts. For this reason, the Corporate Tax Haven Index ranks jurisdictions according to a combination of their haven score and the volume of multinational financial activity proxied by the jurisdiction’s share in global inward and outward FDI.

An advantage of the index is the broad coverage of regulatory aspects which go beyond the general features of the corporate tax system and which might be relevant especially for analyses of MNEs’ tax avoidance. In this regard, the extensive documentation is an additional pedagogical asset. A potential disadvantage is the short time coverage which limits intertemporal analyses.

The Tax Attractiveness Index developed by the Institute for Taxation and Accounting at LMU Munich (Schanz et al., 2017) captures information on statutory tax rates and a broad range of general tax provisions at the corporate level such as capital allowances, loss treatment, and the availability of special tax incentives as well as tax provisions at the shareholder level. The index evaluates the tax provisions’ generosity from the company’s point of view where a high index value implies fewertax payments or less administrative costs and thus a greater tax attractiveness. Some of the tax provisions are rated in relation to other countries’ provisions. Accordingly, variation in a country’s index value may occur even if a country does not change its tax laws but just because other countries do, which is a suitable manner of operationalising the effects of international tax competition. An advantage of the Tax Attractiveness Index is its relatively long time coverage reaching back until 2007 which facilitates intertemporal and statistical analyses.

Ceci pourrait également vous intéresser

Tax deficits and the income shifting of U.S. multinationals

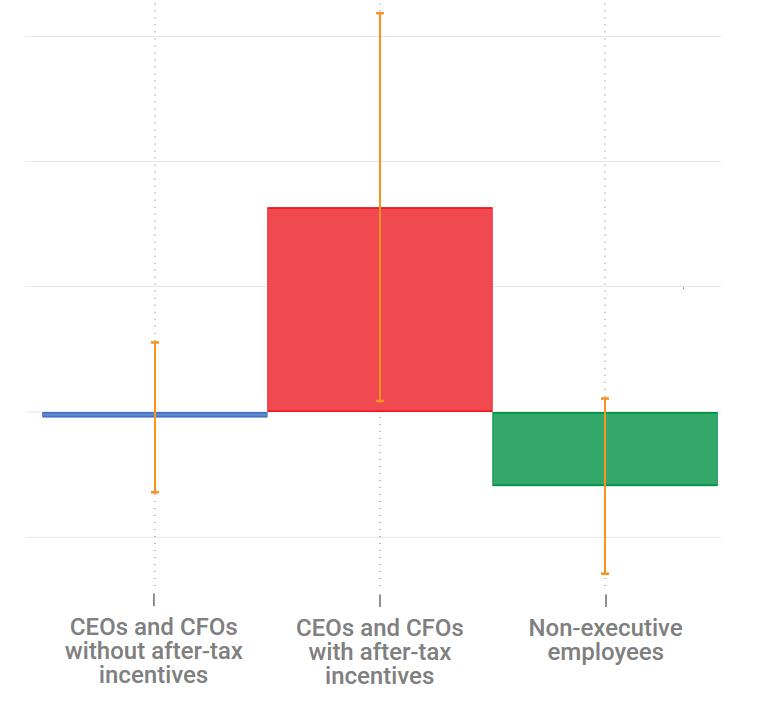

Profit shifting, employee pay, and inequalities: evidence from US-listed companies

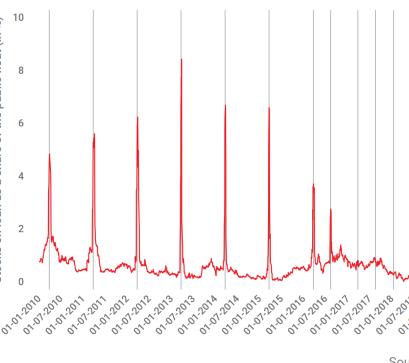

Welfare Effect of Closing Loopholes in the Dividend-Withholding Tax: The Case of Cum-Cum and Cum-Ex Transactions