The new luxury freeports: Offshore storage, tax avoidance, and ‘invisible’ art

Escaping the Exchange of Information: Tax Evasion via Citizenship-by-Investment

Summary

Langenmayr and Zyska provide indirect evidence that very wealthy tax evaders avoid international tax transparency measures by making use of citizenship-by-investment (CBI) programs. Due to the recently adopted automatic exchange of information on financial accounts, most countries exchange information of bank accounts held by non-residents in order to detect cross-border tax evasion. CBI programs offered by tax havens help circumvent this new regulation. For example, the Dominican citizenship can be obtained in exchange of a 100,000 USD donation to a governmental agency without any residency requirements. A German resident could obtain a Dominican passport and use it to open a Swiss bank account. The Swiss bank account will officially be owned by a Dominican and thus not be of interest to the German tax authorities even though the holder actually lives in Germany.

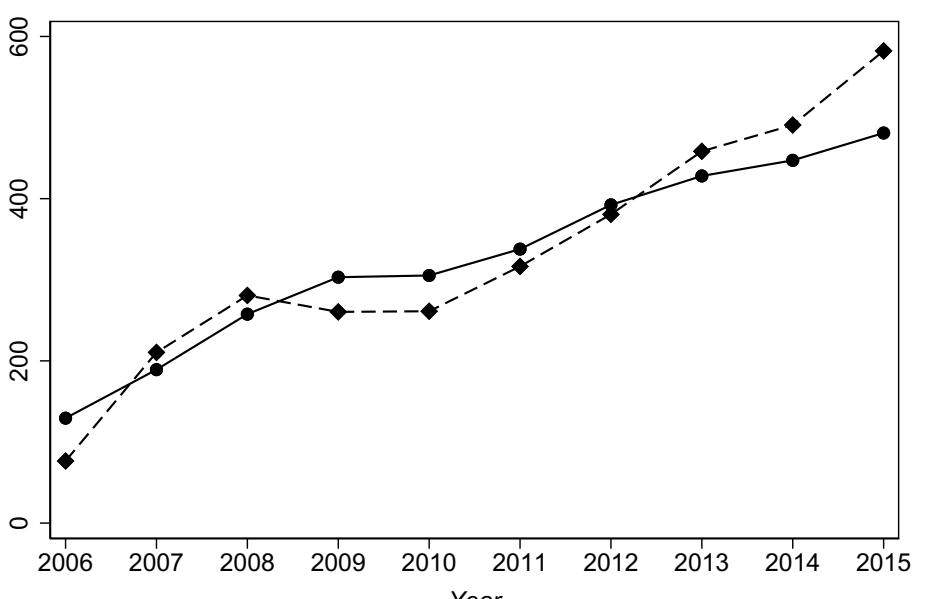

Based on the Locational Banking Statistics from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the authors compare the development of bank deposits in tax havens and non-havens held through jurisdictions with CBI programs. The regression analyses show that tax haven deposits held though 6 jurisdictions with high-risk CBI programs increased significantly just after these CBI programs had been put in place. This suggests that tax evaders might have used the CBI programs to conceal their ownership of tax haven deposits from their domestic tax authorities. In contrast, the authors do not find similar results for the introduction of residency-by-investment programs, suggesting that their use for tax evasion purposes might be less common.

Key results

- Cyprus, Dominica, Grenada, Malta, St. Lucia and Vanuatu have implemented high-risk citizenship-by-investment programs in the last years or made them more attractive. (Note: The Cypriot program was discontinued at the end of 2020)

- The authors estimate that bank deposits from these high-risk CBI countries in tax havens have increased by 48 to 55% after the introduction or reform of the CBI program providing indirect evidence that tax evaders use these programs.

- This increase represents circa 25% of CBI countries’ GDP, 9 billion USD in absolute amounts, or 0.66% of total offshore bank deposits based on the estimate of Zucman (2013) for the year 2008.

- As the sample comprises only ten tax havens, the estimated amount of deposits hidden via CBI is likely to be a lower bound estimate.

Policy implications

- Langenmayr and Zyska explain that although only approximately 40,000 individuals were found to use the high-risk CBI programs considered, their very high net worth suggests that the phenomenon is of significant scale.

- The authors highlight the necessity to account for CBI opportunities when establishing or reforming tax information exchange programs. For example, banks in tax havens should be required to establish the tax residency of their customers based on several documents and not only through passports from CBI countries. In addition, CBI countries might be required to inform the tax administration of the initial country of origin when the new citizenship is being granted.

Data

The authors use Locational Banking Statistics from the Bank for International Settlements (read more). More precisely, they use bilateral data on the deposits held by non-banks in 30 countries over the 2010-2018 period.

Methodology

Langenmayr and Zyska estimate various regression models and complement them with an event study approach.

Go to the original article

The original article was published by CESifo and can be accessed via the website of the CESifo.

This might also interest you

Transparency and Tax Evasion: Evidence from the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA)

Breaking Bad: What Does the First Major Tax Haven Leak Tell Us?

Channels of tax evasion